Monthly Archives: July 2015

Check out

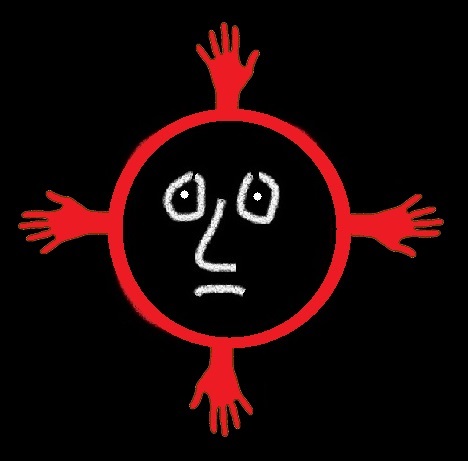

“The idea of control”

Addicted Minds.

Leave a comment | posted in control

Earlier I described how they trap monkeys in Asia by placing bait in a heavy jar with a narrow neck. The monkey smells the bait, reaches in to grab it, and traps himself by refusing to let go.

The monkeytraps to which humans are vulnerable are psychological — situations that trigger us into holding on when we really should let go.

And how can you tell when you’re approaching entrapment?

Three tips:

.

Tip 1:

Notice where you’re uncomfortable.

We’re controlling whenever we need or want to change some piece of reality instead of accepting it or adapting to it as is. And we’re most likely to want to change the realities that make us uncomfortable. So it makes sense that our discomfort zones are where we’re most likely to get monkeytrapped.

![[] bert panel (print for edit)](https://monkeytraps.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/bert-panel-print-for-edit.jpg?w=490) Bert: Personally, I hate rejection. So I’m most controlling with people I think might reject me. I hide feelings I think will upset them, pretend to agree when I really don’t, avoid confronting behavior I dislike, laugh at stupid jokes, and so on and so on. It keeps me busy.

Bert: Personally, I hate rejection. So I’m most controlling with people I think might reject me. I hide feelings I think will upset them, pretend to agree when I really don’t, avoid confronting behavior I dislike, laugh at stupid jokes, and so on and so on. It keeps me busy.

.

Tip 2:

Notice where you’re stuck.

Stuck as in not learning, healing or growing — struggling with the same problem over and over. You know you’re monkeytrapped whenever you find yourself doing what you already know doesn’t work, but can’t think of an alternative.

![[] bert panel (print for edit)](https://monkeytraps.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/bert-panel-print-for-edit.jpg?w=490) Bert: All that controlling I just described traps me because it (a) stops me from being myself, which (b) prevents me from ever getting accepted as myself, which (c) keeps me chronically scared of rejection, which brings me right back to (a). It’s like riding an endless merry-go-round.

Bert: All that controlling I just described traps me because it (a) stops me from being myself, which (b) prevents me from ever getting accepted as myself, which (c) keeps me chronically scared of rejection, which brings me right back to (a). It’s like riding an endless merry-go-round.

.

Tip 3:

Notice where you’re scared.

Like all addictions, compulsive controlling is anxiety-driven. We stay monkeytrapped because we’re scared to do anything else. Often even the thought of giving up control in such situations is enough to scare us silly.

![[] bert panel (print for edit)](https://monkeytraps.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/bert-panel-print-for-edit.jpg?w=490) Bert: It took me decades to see that controlling doesn’t work. Or that it does, but only for five minutes at a time. Then another scary thing comes along and I have to control that. And life being what it is, there’s no end to scary things. So as an anxiety-reduction tactic controlling is a total flop.

Bert: It took me decades to see that controlling doesn’t work. Or that it does, but only for five minutes at a time. Then another scary thing comes along and I have to control that. And life being what it is, there’s no end to scary things. So as an anxiety-reduction tactic controlling is a total flop.

The most frightened people are the most controlling people.

And it is the most controlling people who remain the most frightened.

2 Comments | posted in control

-

The healthiest anyone gets is neurotic.

Thus spake my first supervisor.

I was dismayed. Back then, as both a new therapist and a recovering depressed person, I clung to the idea of mental healthiness the way a sinner clings to the idea of redemption.

But decades later I know he was right.

Neurotic means split into two parts: one public, one private. You create neurosis by convincing a person that it is neither acceptable nor safe to be him- or herself.

This happens to everyone. It is the inevitable result of socialization and other forms of conditioning which teach us not to be ourselves.

Think of it as what happens when two sets of needs collide.

We each need to function as autonomous individuals, to operate in ways that meet our individual needs. Some needs are physical (food, shelter, etc.), some psychological, some emotional. We have a psychological need to establish ourselves as unique individuals, for example, (see the discussion of separation and individuation in Chapter 28) and an emotional need to express how we feel (see Chapters 24 and 25 on anxiety and depression).

Call these the self-needs.

At the same time we’re also social animals with social needs. We need contact and connection with other people, need their acceptance, approval, affection, protection and support. No less than the self-needs, these social needs define what it means to be a human being.

But getting social needs met can be costly. Even if we grow up in a reasonably healthy family able to love and accept us unconditionally, the world outside is less gentle. There we face inevitable demands to adapt and conform, to redefine and disguise ourselves according to what the tribe expects. And we have no choice but to comply.

When I work with couples I explain that all relationships are difficult because they force us to wrestle endlessly with two questions: How can I have you without losing me? How can I have me without losing you?

Every socialized human being struggles with the same questions. How can we satisfy self-needs and social needs at the same time? How can we belong to the larger tribe without losing what makes us unique individuals?

So pervasive is this struggle that it can blur the boundaries that define us. For many it becomes hard to tell where we end and the rest of the world begins.

I’m mad at Dad. But if Dad knows I’m angry he may reject me, and I’m scared of that. I’m afraid it would leave me feeling hurt, guilty, inadequate, abandoned and/or disinherited. So I hide my anger in self-defense.

Am I controlling myself in order to control Dad? Or am I controlling Dad in order to control myself?

Thus I get split into two selves, private and public, real-me and false-me, controller and controlled.

And my boundary gets blurred, and after a while I can’t tell who I really am, what I really need, or how I really feel.

Again, nobody can avoid the tension between self and environment.

Which means neurosis happens to all of us.

Which means it’s normal to end up split, and scared, and trapped by the control addiction to which neurosis gives birth.

Which means we’re all monkeys on this bus.

9 Comments | posted in control

![[] bert panel (print for edit)](https://monkeytraps.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/bert-panel-print-for-edit.jpg?w=490) Bert: Personally, I hate rejection. So I’m most controlling with people I think might reject me. I hide feelings I think will upset them, pretend to agree when I really don’t, avoid confronting behavior I dislike, laugh at stupid jokes, and so on and so on. It keeps me busy.

Bert: Personally, I hate rejection. So I’m most controlling with people I think might reject me. I hide feelings I think will upset them, pretend to agree when I really don’t, avoid confronting behavior I dislike, laugh at stupid jokes, and so on and so on. It keeps me busy. ![[] bert panel (print for edit)](https://monkeytraps.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/bert-panel-print-for-edit.jpg?w=490) Bert: All that controlling I just described traps me because it (a) stops me from being myself, which (b) prevents me from ever getting accepted as myself, which (c) keeps me chronically scared of rejection, which brings me right back to (a). It’s like riding an endless merry-go-round.

Bert: All that controlling I just described traps me because it (a) stops me from being myself, which (b) prevents me from ever getting accepted as myself, which (c) keeps me chronically scared of rejection, which brings me right back to (a). It’s like riding an endless merry-go-round.![[] bert panel (print for edit)](https://monkeytraps.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/bert-panel-print-for-edit.jpg?w=490) Bert: It took me decades to see that controlling doesn’t work. Or that it does, but only for five minutes at a time. Then another scary thing comes along and I have to control that. And life being what it is, there’s no end to scary things. So as an anxiety-reduction tactic controlling is a total flop.

Bert: It took me decades to see that controlling doesn’t work. Or that it does, but only for five minutes at a time. Then another scary thing comes along and I have to control that. And life being what it is, there’s no end to scary things. So as an anxiety-reduction tactic controlling is a total flop.